If you follow this blog, you may know I'm interested in fictional tropes about eunuchs.

Here's one I just found:

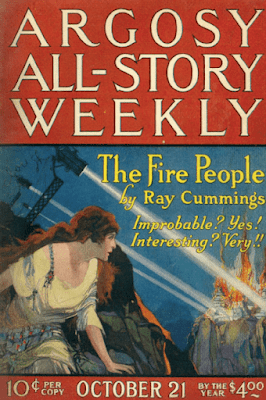

The novelette "Down the Coast of Barbary" by H. Bedford-Jones was published in Argosy, October 21, 1922. pp. 500–537. Read it on PulpMags.org in the flipbook or download the PDF.

On May 3, 2025, I wrote a better version of this material for Medium, so you may want to check it out there.

Chapter 1

A young Captain Patrick Spence is an American stranded penniless in Algiers after a shipwreck and resettled locally next-door to the Dey of Algiers by helpful Englishmen. The place is "a hotbed of intrigue. Spanish armies were holding Oran against the Moors and the land was in turmoil."

In 1730, Spence finds a Punic coin in his villa garden. He brings the Rev. Dr. Shaw, who is from Oxford, to have a look at it.

Spence says: "Shaw, something's happened! Here's one of the consulate negroes on the run!" Bedford-Jones clarifies: "He was a black man. His nearly naked skin glistened with sweat." He is "panting" and speaks "in a chatter of Arabic" that Shaw understands. Shaw leaves with the man.

Two more people arrive at Spence's villa: a thin old man with "a mustache and goatee of grayish black" and "black eyes that blazed like jewels [and] held weird fires in their depths," who is wearing the royal ornament of "the glorious collar of the Golden Fleece." A woman in a silk dress is traveling with him. They stop to say hello. He identifies them as Spaniards, and they tell him he may stay with them in Morocco anytime he likes.

Next, Mulai Ali the Idrisi, described as a Moor, stops by and asks Spence if he knows a man named Ripperda. He says he's spoken to the astrologer of Arzew and their fates are linked. He offers Spence money, power, and a wife. Spence says he doesn't want payment, but "if my help will avail you, I give it freely." The man asks: "Will you go to Morocco with me? Think well! The stars have promised me success." Spence shrugs and says yes. Mulai Ali gives him a box and an unsigned note from someone who identifies himself as a slave and says "I have woven a net to catch Ripperda." Mulai Ali warns Spence to beware of a man in a black burnoose.

Chapter 2

We're informed that the Moorish provincial government is at Arzew, “the ancient Arsenaria, twenty miles east of Oran.” It's under Hassan Bey, a Turk.

We also learn that William Lewis de Ripperda was "born a Roman Catholic baron of Holland," then changed religions opportunistically, becoming ruler of Spain and then Morocco. He seeks "to form a coalition of the Barbary States against Christendom." The consul warns Spence: "unless we destroy Ripperda, this Ripperda will destroy Spain and Christendom!" Mulai Ali says: "Ripperda commands the Moslem armies before Oran; the Dey dare not offend him."

Mulai Ali invites Spence and Shaw on this quest to defeat Ripperda "because you are true men. And through you I can make treaties with England..." They agree to join him, Spence just because he feels like it and Shaw because he expects it will be a voyage through lands of archaeological interest.

Before they leave, Spence sees a man in a black burnoose with “a twisted face that was marked by a purplish birthmark about the right eye.” Soon after, the man jumps him, but other men, including "the consulate negro" with his scimitar, chase him away.

Chapter 3

They ride west, beginning their quest. Spence has sewn the mysterious box in cloth and tied it to his saddle.

Mulai Ali's scheme is to grab the throne while Ripperda is away joining the army at Oran.

They stay at the citadel [kasbah] of Hassan Bey.

We learn that the man in the black burnoose is Gholam Mahmoud, a former Janissary who serves Ripperda. We also learn that the astrologer is an Englishman, captured by Hassan from an English ship and kept by him as a slave. Mulai Ali wants Spence to release the astrologer from Hassan's clutches. Mulai Ali himself will not do it, on the religious principle that he has accepted Hassan's hospitality, but he expects that "a Christian has no scruples."

In the kasbah courtyard, in a pomegranate grove, "a huge black eunuch, half asleep," armed with a scimitar, guards a stone tower. He recognizes Mulai Ali and lets them in the tower where the astrologer is held captive. Inside, Spence is astonished to learn that the astrologer is a beautiful young girl, Elizabeth Parks.

Elizabeth tells Mulai Ali that he is destined to live no more than ten years and die violently if he persists in his way of life. He says that's quite all right with him.

Spence understands that the girl “had seized one slim hope of escaping the harem; how she had worked upon the besotted and superstitious Hassan Bey until he feared her more than he desired her.” Mulai Ali tells Spence that this is the bride he'd promised, should Spence want her, and that the eunuch will help the girl escape with them because the eunuch has hope of improving his own position, perhaps becoming chief eunuch in a sultan's harem.

Spence is to depart with the astrologer that night, and everyone else — Mulai Ali, Dr. Shaw, and the eunuch — will leave the next morning. In part, this is so Mulai Ali can communicate with the eunuch. "I know no Arabic, and I fancy the eunuch has no Spanish," Spence explains.

Chapter 4

While Hassan Bey is debauching at a party, Spence slips away to rescue the astrologer. “...a dark shape arose before him, the starlight glittered on a naked blade, and he recognized the distorted shape of Yimnah, the eunuch,” who is named here for the first time. Spence tells the astrologer that they’ll ride to Tlemcem. There are five in their party, each on their own horse: Yimnah, Elizabeth, Captain Spence, and two Spahis assisting them.

A stranger on horseback shoots at Spence, but Spence shoots back and kills him. He takes a written note off the man's body. The Spahis are able to read it. It suggests that spies are aware of Mulai Ali's location and direction of travel.

They hear a Spanish man singing. “The eunuch, Yimnah, baring his scimitar, slipped from the saddle and glided forward to the masking trees. Then he was back, his thick lips chattering words of fear, his limbs trembling.” Elizabeth translates for Spence: “He says it is the ghost of Barbarossa.” Then they see the Spaniard: the large, red-headed Lazaro de Polan, who says he is sometimes called Barbarroja. He says he is a capable fighter, and he asks Spence to hire him for his quest. Spence agrees.

Chapter 5

Outside their inn in Tlemcen, Spence briefly sees Gholam Mahmoud hiding in the shadows. Spence angrily throttles the innkeeper, demanding that he find Gholam Mahmoud, but the innkeeper denies any knowledge of the man.

Spence and Yimnah share a room. Yimnah snores. Early the next morning, Yimnah hears the call from the minaret and rises for his morning prayers. Spence sees Gholam Mahmoud on the ground and he jumps out the window.

Spence is tied up, and Barbarroja negotiates with Gholam Mahmoud. Gholam Mahmoud's arms are bare, revealing a dolphin tattoo on the right arm. This reveals him as a Janissary in the Thirty-first Orta (cohort), a bodyguard to the sultan. Barbarroja tells him he knows where the little leather casket is, and suggests he might be willing to sell it to Ripperda. Gholam Mahmoud seems nervous that the sherif might know about its existence; Barbarroja says he does not. Gholam Mahmoud says he's on orders from Ripperda "to kill Mulai Ali before he reaches Udjde, and to regain the box of leather." Barbarroja convinces Gholam Mahmoud that they both want to kill Mulai Ali, though for different motivations. He asks Gholam Mahmoud what he wants from their alliance, and Gholam Mahmoud asks for the girl, to which Barbarroja readily agrees.

Returning, Barbarroja trips over Spence's bound body. He cuts him loose. Spence asks if he's seen anyone with a twisted face. Barbarroja says the man left on a horse a half-hour earlier. The narrator indicates to us that Barbarroja is fooling Spence but will receive his comeuppance.

Chapter 6

Spence sends Barbarroja and "a Spahi" to meet Dr. Shaw, and in their absence, he flirts with Mistress Betty, asking her to draw up his horoscope. He tells her he knows that Gholam Mahmoud is near. She replies that if Mulai Ali comes to Morocco, he'll easily take the throne from the current sherif, who is "a mere tool in the hand of Ripperda."

Barbarroja tells Spence that Mulai Ali is waiting for him, so he and the girl ride out of Tlemcen, meeting up with Mulai Ali and Shaw at a rest stop for water and a smoke. Mulai Ali says he's willing to face Gholam Mahmoud alone, and counsels Spence, Shaw, Mistress Betty, "taking Barbarroja and two of the spahis," to seek safety in Udjde. He wants Spence to take the leather box, with its "copies of secret Spanish treaties," for safekeeping. Yimnah also comes to Udjde, "bringing up the rear."

On the way, Shaw asks Spence what he's decided to pay Barbarroja, since "you told him you would discuss wages with him at Tlemcen." Spence admits that he "forgot" to do so. Shaw makes a vague comment: "If the man were what he seemed — well, well, let be."

They stop briefly at a place called El Joube (The Cisterns). Here, Barbarroja threatens them, offering "peace or war." He tells them that they're about to be ambushed, but he can call them off if they hand over the girl. "Now, how much is she worth to you?" Dr. Shaw replies: "Villain!" and knocks Barbarroja unconscious. Barbarroja's hidden allies fire on the party with muskets, but they escape on their horses.

Chapter 7

One of the mounted Spahis grabs the halter of Betty's horse and races away with her. Another leaps into the saddle of Barbarroja's horse. Shaw slays one of his aggressors with a sword. Spence shoots two with a pistol.

A wide blade flamed in the moonlight. The hoarse, inarticulate rage scream of Yimnah rent the night like a paean of horror. The monstrous figure of the eunuch, streaming blood from a dozen wounds, rushed through the assailants, striking to right and left in blind fury. They opened before him, fell back from Spence, shrieked that this was no man, but some jinni of the mountains. Yimnah leaped on them, struck and struck again, screaming.

'Fools!' cracked out a voice in Spanish.

A musket flashed near the voice. There died Yimnah, the wide blade sweeping out from his hand and clashing on the stones.

The voice belonged to Gholam Mahmoud. The injured Barbarroja crawls back and argues with Mahmoud: ‘Now Spence is escaped and Mulai Ali not come. Pot-head that you are—only one eunuch bagged, and half our men down!’ He insisted: ‘I stay here to kill Mulai Ali when he comes.’ Gholam Mahmoud rides alone to Udjde.

Spence meets an Englishman who had been a cutpurse in Bristol, was conscripted into the navy, and was captured by “Algerines” and enslaved for 30 years. The man gives him directions to Udjde. After the man leaves, Spence spots Ripperda with his bodyguard, riding to Udjde.

Chapter 8

Two Spahis — “dour, bearded Turks” — are riding with Mistress Betty, one on each side of her, each holding onto her horse’s reins. Shaw, still holding his rapier, catches up with them. Betty chides him for abandoning Captain Spence in battle. He sheaths his rapier and tells her that he must carry an important letter “involving the fate of empires and of religions” to the Governor of Udjde — so that Pasha Ripperda will not remain ruler of Morocco, the Barbary States won’t attack Spain and the Moors won’t start a holy war to take it back — and that Mulai Ali’s welfare also depends on him completing his errand. So they all continue to Udjde, where they are given hospitality and Shaw dines with the governor. The governor tells him something about Mulai Ali’s adversaries: Barbarroja serves the Sherif Abdallah, and the man in the black burnoose, Gholam Mahmoud, serves Ripperda. Just then, two slaves bring a carrier pigeons with messages, one warning the governor that Ripperda will arrive tomorrow with his bodyguard, the other notifying him that Mulai Ali has been shot dead. The governor plans to receive Ripperda. Shaw says he will stay and hope that Ripperda will spare him because he has “a nominal errand to the sherif.”

Elsewhere in the town, Gholam Mahmoud sits at home, awaiting Barbarroja, who arrives, saying: “I rode my horse to death and walked the last two miles of the way here.” He then claims that he was the one who shot Mulai Ali in the back, and says he’ll permit Gholam Mahmoud to tell the pasha that they killed Mulai Ali together so that he can share credit, but he says he wants to keep the full amount of the reward from the sherif. He also reveals that Spence, whom he expects to travel west through their region, "carries the leather box behind his saddle." Gholam Mahmoud negotiates: he says he’ll let Barbarroja have the money if he will kidnap the woman Gholam Mahmoud wants. Barbarroja begins to plot how he'll get her.

Chapter 9

Shaw awakes with a change of plan. He's stressed. (He has received a letter in English signed by Spence, saying that he's been wounded, has no horse, Mulai Ali is dead, and he fears to enter the city. He asks to meet him at the deserted tomb of Osman, a half-mile from the city gate.) Shaw tells the governor: "I will take the two Spahis who brought me here and go on to Fez." The governor doesn't care much why; he's just relieved that Shaw is leaving before he has to deal with Ripperda. Shaw, the two Spahis, Mistress Betty, and a guide ("a rascally one-eyed Moor") head toward the western gate of the city. Just as they exit the western gate, they hear a crowd cheer as Ripperda enters the city by the northern gate.

The tomb of Osman was a trap. Both Spahis are slain, one by the guide with a long knife, the other by three men waiting in ambush with muskets. One of these men is Barbarroja, aka Lazaro de Polan, who crows that he forged the note pretending to be Spence. Meanwhile his men "plundered the dead Spahis." Barbarroja tells Shaw he wants "the pretty señorita," but he says "I owe you a debt for what you did to me at the Cisterns, and I shall settle the debt. ... And you are in my power, and my friend Gholam Mahmoud will take the leather box when Spence shows up, as he must soon do!" He recaps: "You insulted me both in Christian and Moslem fashion. ... You kicked me, for which the ancestry of Lazaro de Polan demands recompense; and you tweaked my beard, for which the ancestry of Barbarroja demands vengeance."

Shaw calls him a "vile renegade": "Dog that you are, I suppose you will have your bandits pistol me in the back!" They begin to fence. Shaw slays Barbarroja, whose three men flee.

Spence then arrives, saying the governor had suggested he come to find out if anything was wrong with Shaw and Mistress Betty. Spence's men (Ripperda's guard) chase after Barbarroja's men.

Shaw recovers Barbarroja's 800-year-old blade, the Toledo, from his fallen body.

Spence tells Shaw that Ripperda wants him. Shaw replies that Gholam Mahmoud is aware that Spence carries the casket behind his saddle, as Barbarroja had told him. Spence assures him that he's already thrown the box into the river.

Spence's men return with the three severed heads of Barbarroja's men. Spence, Shaw, and Mistress Betty ride back to Udjde.

The narrator informs us that Mulai Ali isn't really dead.

Chapter 10

Pasha Ripperda, suffering from gout, believes that Mulai Ali is dead. "This thin man with the haunted eye was the supreme ruler of western Africa; the combined Barbary armies and fleets obeyed his orders — Egypt was in alliance with him."

Spence, Shaw, and Mistress Betty enter the justice hall of the kasbah, and he greets them, though he is barely able to rise. Ripperda, "generous enough in victory," offers to forgive and forget, and Shaw accepts. The three travelers go their guest room. Spence and Shaw smoke pipes "with the girl's permission," as she listens to their conversation.

Spence describes how he cast away the box and found Ripperda "friendly enough." Shaw says: "Mistake not, Patrick; we play with fire." To which "Spence shrugged."

Out the window, they observe activity in the courtyard. Ripperda's guard forbids them to leave their room. Gholam Mahmoud has arrived — "Ripperda's confidential agent," who must have "heard of Barbarroja's death," Shaw muses. Spence acknowledges that Ripperda's men probably saw him cast the box into the river.

Pasha Ripperda's bodyguard fetches Mistress Betty on the pretext of wanting an astrological reading. Spence and Shaw must stay in the room; the narrator hints that one may soon die.

She witnesses Gholam Mahmoud, "a tall figure in black," approach Ripperda. She doesn't hear their conversation. Gholam Mahmoud whispers his offer: he'll attempt to fetch the box, and he asks for Mistress Betty "for my harem" if he succeeds in finding it. Ripperda replies: "Her and a dozen more like her....The girl belongs to you." He'll wait at Adjerud to hear the results.

Ripperda tells her he has no intention of giving her friends mercy. She asks anyway, and Ripperda says he'll sell Spence into slavery in Adjerud as a form of mercy, but he'll execute Shaw for knowing and keeping secret that "the box was gone, that I was defeated, unable to keep my promises." He then asks Mistress Betty to tell his horoscope. He lies: "you are under my protection and shall go safe to England. You have the word of Ripperda." She can tell it's a lie, so she asks for a week to prepare his horoscope. He locks her up with two female servants.

"Spence and Dr. Shaw, disarmed and bound, were dragged forth besides Ripperda's litter. From his curtained cushions, Ripperda glared out like some venomous reptile at Shaw." Mistress Betty has a litter alongside Ripperda. Betty's perspective is not mentioned, but Spence and Shaw understand the respective fates of all three of them. "Spence was tied into a high saddle," Shaw is "dragged away," and the two men shout their goodbyes.

Chapter 11

Adjerud is a prosperous small town on the Tafna River. Ripperda's ship is in port, rumored to contain his treasures. A second ship, the "Boston Lass," from "a far country," is also there, in need of repairs, and that's where Spence is enslaved with other Americans. Betty is kept in a tent near Ripperda, and she's allowed to leave under guard. On Friday, he asks for the horoscope. She tells him she sees death and needs one more day to finish it. He says that Algiers, Egypt, and Admiral Perez have just joined his side.

That night, outside her tent, a messenger from Udjde delivers a message to her (her guard pays the messenger). It's a message from Shaw, who says that Mulai Ali is alive, marching on Fez, and about to be named sherif. He adds that the messenger is backed by Mulai Ali to attempt to rescue her and Spence. Betty assumes she'll be second priority in the rescue effort or that it will be less feasible to rescue her, and meanwhile she plans to use the astrological reading to tell off Ripperda, even if he kills her for it.

The next day, she sees Gholam Mahmoud enter Ripperda's tent. She doesn't see what happens inside. Gholam Mahmoud has retrieved the box. Ripperda opens it, finds "a number of small packages wrapped in oiled silk," and is satisfied. Gholam Mahmoud demands his reward, and Ripperda says that after the girl reads his horoscope tonight, he'll be free to take her.

That night, in front of the two men and one guard, with Gholam Mahmoud smoking a water pipe, she tells Ripperda: "Your star has waned, my lord. The war against Spain is doomed to failure — nay, has already failed! Mulai Ali is alive and has been proclaimed sherif. You yourself have not a fortnight longer to enjoy life — "

Ripperda swears, interrupting her, but just at that moment, he receives a message of defeat from Admiral Perez. Algiers is defeated, Pasha Ali is dead, and he asks Ripperda to flee to Tetuan on the coast. A moment later, another messenger arrives that Mulai Ali is marching on Fez, backed by the Zenete tribes, and that Spanish ships are heading to Oran.

Ripperda wants to sail for Tetuan, but they hear the crowd shouting for "Ras Ripperda!" ("Ripperda's head!"), and it seems impossible to access the ship. Ripperda and his men flee on horseback. Gholam Mahmoud orders his men to raid the treasures on Ripperda's ship.

Chapter 12

Aboard the Boston Lass, the men (three from Newfoundland, the rest from Boston) are chained at their wrist and ankles. As the masses are shouting for Ripperda's head, the Spaniards unchain them and give them robes (burnooses) and scimitars to disguise them so they will not be perceived as escaping Christian slaves. Spence seems to be the natural leader of these freed men. They realize they need Ripperda's ship to escape. As they see someone else taking the ship out of port, one man objects: They should not continue standing around waiting for a lady. In reply, "somebody smote the man." Then they hear that Gholam Mahmoud, with about thirty men, has taken the ship with Mistress Betty on it, so they find smaller boats and row after it, catch up, and climb onto the deck, slaying the men who rush them.

Gholam Mahmoud slays one of the Newfoundland men. Spence breaks the neck of one of Gholam Mahmoud's men. Then he sees Mistress Betty shooting a swivel gun from the starboard rail. Gholam Mahmoud is struck first by Spence, then again in the back by someone else, and he falls overboard. They have won, with only four deaths on their side, and they have Mistress Betty.

Chapter 13

They sail past Tetuan and Gib-al-Taric, and off the coast of Tangier some of them switch, in open water, to another boat. They divide Ripperda's gold. Some of the gold is for Mulai Ali, along with the little box that contains the writings with Ripperda's plans. Some of the gold is for Spence's party, who decide to head for Boston rather than London, as they believe they have a better chance of holding onto their gold there. Spence asks Betty if she minds heading to Boston, and she tells him that she feels like Ruth. "Dost not remember what Ruth said to the man in whose hand her own lay — even as mine lies in yours?" she says. I think that's a mistelling of what Ruth said to Naomi (Your people shall be my people, I go where you go. Ruth 1:16) rather than what she said to a man, say, Boaz (Ruth 3:9). But anyhow, the story ends there.

Here's my book.

The perceived connection between eunuchs and magic

According to Lewis Coser, eunuchs’ power operated “over women and children in the recesses of the harem and the court,” and eunuchs tended toward “magic and superstition in the court intrigues” which was “in contrast to the rationalism of the bureaucrats.” Eunuchs “practiced favoritism and particularism while the literati advocated universalistic standards.” That Coser said it does not mean it was necessarily always and everywhere true, nor even sometimes and somewhere. I cite him to describe this common perception. It is a binary perception of men as rational and eunuchs as irrational.

"The Political Functions of Eunuchism." Lewis A. Coser. American Sociological Review, Vol. 29, No. 6 (Dec., 1964), pp. 880-885 (6 pages) https://doi.org/10.2307/2090872 https://www.jstor.org/stable/2090872 Quotation from p. 882.

Background information (Coser 1972 journal article)

“The alien as a servant of power: Court Jews and Christian renegades.” Lewis A. Coser. American Sociological Review 1972, Vol. 37 (October):574–481. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2093452

The Ottoman princes preferred to be served by foreigners, since “they are so far removed from him in the status order they can never threaten his rule.” (Coser 1972, p. 574).

“I showed in an earlier paper (1964, cf. also Hopkins, 1963) that political eunuchs can be seen as prototypical servants of power because they lacked roots in the social structure and hence depended on the oriental monarchs who used them. Being typically recruited from young children taken in war raids on the periphery of the Empire and then castrated, they had neither effective families of orientation nor of procreation. They could establish no ties in the community, and their loyalty was available to the monarch. There are, however, many cases where uncastrated members of alien communities served absolutist power. Such aliens, although sexually potent, were as politically impotent as the eunuchs.” (Coser 1972, p. 575) [The full citation for Hopkins: Hopkins, Keith. 1963. “Eunuchs in politics in the later Roman Empire.” Proceedings of the Cambridge Philological Society 189 (New Series, No. 9):62–80.]

A court Jew, for example, served at the pleasure of the prince. “There was no security of tenure…nor could the Court Jew transmit the position to his descendants… Specific Court Jews served specific princes on a particularistic basis.” This made sense, according to “the economic historian David S. Landes (1960:205),” when “the credit of the state was weaker than that of the banker.” They became obsolete when banks modernized in the 19th century. (Coser 1972, p. 577) Court Jews resembled “political eunuchs of the Eastern world and celibate priests of the Catholic Church. Though they had families of their own, these families were as effectively cut off from the surrounding world of the gentiles as individual eunuchs or celibate priests were from the community and kinship that grow from sexual union.” (Coser 1972, p. 578)

“In its early stages, the Ottoman Empire was based on a relatively unstable balance between the Sultan’s forces and his civilian and military bureaucracy, and ‘feudal’ and aristocratic land owning strata. (Eisenstadt, 1960:288.) ...they fashioned a most peculiar civilian and military administration consisting almost entirely of non-native recruits unattached to the native Muslim population. * * * Between 1453 and 1623 only five of the forty-seven grand viziers were of Turkish origin.” (Coser 1972, p. 578) For Christian renegades, “no office was hereditary.” Generally, they had to retire before they could marry, and their sons were ineligible for a court job at all. (Coser 1972, p. 579) [The full citation for Eisenstadt: Eisenstadt, S. N. 1963. The Political Systems of Empires. New York: The Free Press.]

Whereas, for “the most intimate functions performed for the sultan” in his home, it wasn’t enough to be a foreigner; the sultan demanded that the servant also be castrated. (Coser 1972, p. 580 — he cites Lybyer, 1966:56ff and 123ff, but unfortunately the part of Coser's bibliography that would have the full Lybyer citation is cut off from the JStor scan.)

In China, “they represented the very antithesis of the principle of inheritance upon which any aristocratic status group necessarily rests. They were trustworthy since they could never covet hereditary power.” And consequently “their very position rested upon the rejection of aristocratic principles just as it made them consistent opponents of bureaucratic principles.” And so they were the emperor’s “instruments” when he “wished to escape the control of both gentry and bureaucracy.” (Coser 1964, pp. 883–884)

Coser (1964) points to Karl August Wittfogel, Oriental Despotism (1963) and “History of Chinese Society (1949) with a footnote: “Wittfogel is the only writer I know of who interprets political eunuchism in roughly the same manner I do here…I…profited a great deal from his erudite and perceptive discussion [in Oriental Depotism].”

Coser — born Ludwig Cohen in Berlin, 1913 — died in 2003 at age 89. An obituary in the Brandeis Sociology Newsletter says he had been "the founding chair or our department in the early 1950's."

See also

A new release in 2025: Yufei Zhou's The Science of Oriental Society: Karl August Wittfogel and the East Asian Intellectuals discussed (as per the book description) "how Wittfogel's controversial concept of "Oriental society" has influenced the assessments and interpretations of Asia's economy and society by generations of East Asian social scientists throughout the twentieth century."